Fast days in Judaism are, as Maimonides wrote, days in which we “we yell out with prayers and supplicate.” The purpose of fasting is not to suffer from hunger, but to open up space and time for spiritual reflection by freeing ourselves from tending to our physical needs. Without food in our bodies, it becomes harder to see ourselves as mighty. We are forced to rely instead on the Almighty.

This idea is reflected in the special Aneinu (“Answer Us”) prayer that is added to the silent Amidah on fast days. The prayer asks God to comfort us in our distress, to draw close and to heed our cry.

Answer us, Lord, answer us on our Fast Day, for we are in great distress. Look not at our wickedness. Do not hide Your face from us and do not ignore our plea. Be near to our cry; please let Your loving-kindness comfort us. Even before we call to You, answer us, as is said, ‘Before they call, I will answer. While they are still speaking, I will hear.’ For You, Lord, are the One who answers in time of distress, redeems and rescues in all times of trouble and anguish. Blessed are You, Lord, who answers in time of distress. (Translation from The Koren Siddur)

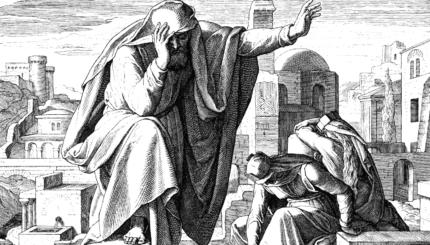

While this kind of prayer makes sense on most fast days, it’s an odd choice for Tisha B’Av, the fast day that commemorates the destruction of both ancient temples, as well as a host of other calamities that befell the Jewish people. Tisha B’Av is a day when, according to our tradition, prayer ceased to be effective, when the gates of heaven were closed to supplication.

In the Book of Lamentations, the mournful text read in synagogues on Tisha B’Av, we read: “And when I cry and plead, He shuts out my prayer.” For this reason, many synagogues customarily omit the line from the Kaddish prayer that asks God to accept our prayers. Tisha B’Av is not a day when prayers are answered.

So why do we recite Aneinu on Tisha B’Av? In fact, why fast at all if fasts are intended to help speed our prayers heavenward?

The answer can be found in another prayer we recite on Tisha B’Av. Nachem (“Console Us”) is recited during the Amidah in the afternoon Mincha service of Tisha B’Av and it differs from Aneinu in that it seeks not an answer from God, but comfort.

The prayer reads:

Console, O Lord our God, the mourners of Zion and the mourners of Jerusalem, and the city that is in sorrow, laid waste, scorned and desolate; that grieves for the loss of its children, that is laid waste of its dwellings, robbed of its glory, desolate without inhabitants. She sits with her head covered like a barren childless woman. Legions have devoured her; idolaters have taken possession of her; they have put Your people Israel to the sword and delibrately killed the devoted followers of the Most High. Therefore Zion weeps bitterly, and Jerusalem raises her voice. My heart, my heart grieves for those they killed; I am in anguish, I am in anguish for those they killed. For You, O Lord, consumed it with fire and with fire You will rebuild it in the future, as is said, ‘And I myself will be a wall of fire around it, says the Lord, and I will be its glory within.’ Blessed are You, Lord, who consoles Zion and rebuilds Jerusalem. (Translation from The Koren Siddur)

Nachem is a prayer that admits defeat. It accepts the reality of failure and loss. The rest of the year, our prayers hold out the promise of God answering our requests. Yet on Tisha B’Av, we confront the stark reality that, at a moment of national catastrophe, our pleas went unheeded.

So what do we do? We continue to pray — not in the hope of being answered, but for the promise of comfort and consolation, to draw close to God even in our time of loss.

One is reminded on Tisha B’Av of the victims of the Holocaust who offered up prayers to God from the ghettos of Europe and the death camps, who organized prayer services on Jewish holidays in the face of imminent death. Facing the horrors of the Nazi genocide, many must have wondered if prayer held the power to redeem them. And indeed, for many it did not. But those prayers, and the faith that underlay them, outlived the Nazi horror.

In his book Rebbes Who Perished in the Holocaust, Menashe Unger relates the story of Rabbi Shalom Eliezer Halberstam (the Ratzfiter rebbe), who was whispering a prayer to God even as the Nazis led him to his death. A Nazi officer asked him: “Do you still believe that your God will help you? Don’t you realize in what situation the Jews find themselves? They are being led to die and no one helps them. Do you still believe in divine providence?” To which Halberstam replied: “With all my heart and all my soul I believe that there is a Creator and that there is a Supreme Providence.”

Eliezer Berkovits, who cites the story in his book With God in Hell, observed: “In the moment before his death, the eighty-two year old Ratzfiter rebbe was more sure of himself and of what he represented in the world than the Nazi officer, behind whom stood all the might of world-conquering Nazi Germany. Rabbi Halberstam was not only expressing the thoughts of one hasidic rabbi, but was formulating the conviction of untold numbers of Jews from all strata of the Jewish people.”

On Tisha B’Av we recall those times in Jewish history when the power of prayer was inadequate to the moment. In acknowledging the suffering of our people, both past and present, we accept that prayer does not always have the capacity to undo all the pain of the world. Yet we still affirm the importance of prayer as a reflection of our deepest held values. Jewish beliefs and rituals have outlasted many enemies who have threatened us. Even in the face of hopelessness, prayer still serves as an anchor of lasting faith.

Mincha

Pronounced: MINN-khah, Origin: Hebrew, the afternoon prayer service. According to traditional interpretation of Jewish law, men are commanded to pray three times a day.